CONTACT US

CONTACT US

by Marc Limacher* and Larry Fauconnet*

ORIGINAL ARTICLE PUBLISHED MAY 2019 IN THE PRAGMATIC

As a product marketer or manager, you may not think of yourself as a CI practitioner. But CI provides actionable intelligence that powers informed product and marketing plans. And naturally, you seek a competitive advantage by being the first to know or access unique, hard-to-find information.

Everyone wants that competitive advantage. But practicing CI collection and analysis requires awareness of the limitations to acquiring and using information that may live in a gray zone — not fully in the public domain, but not a corporate secret, either. It requires great care to understand what information may be legally collected, and how to collect it ethically.

Discussing corporate ethics is commonplace. But mentioning the ethics of CI can set a darker tone. Perhaps the term "intelligence" is the culprit, suggesting shadowy figures engaging in clandestine and espionage activities. This, of course, is a common misconception about CI.

Following are factors to consider in your CI practices — no cloak and dagger needed. At the core, what you can do (legally) and what you should do (ethically) are two sides of the same coin. Both the can and should are guardrails you must consider. Here, we draw on more than 50 years of combined experience as CI practitioners and providers to recommend practical considerations regarding the ethics of CI. As with any recommendations, they should be filtered through your own company's requirements.

For example, in the United States, key relevant federal statutes include the Uniform Trade Secrets Act (UTSA) and the Economic Espionage Act of 1996 (EEA). Both address theft or misappropriation of trade secrets, and violations carry high penalties. There are other U.S. statutes to consider, too. For example, antitrust regulations are an issue if two competing entities discuss market division and/or pricing; and fraud, which generally refers to misrepresenting yourself or your purpose to gain information. Countries outside of the United States have their own — often more restrictive — legal statutes governing these and other factors.

In practice, you may encounter situations in which interpreting statutes like these is open to ambiguity. Along with strictly following your company's requirements, when in doubt, leave it out. It's always better to take the high road. And, though it should go without saying, local statutes addressing inappropriate activities, such as breaking and entering, trespassing and theft, also apply to CI gathering.

The practice of engaging third-party CI vendors on your behalf can carry benefits — from freeing your team's resources for more strategic work to obtaining candid, sponsor-blind information you can't get directly. Remember, though: Your vendor must follow the same laws as your company. If it's proven that you pushed a vendor to violate the law, your company remains responsible. Conversely, engaging a vendor that exhibits questionable conduct themselves can hurt your company's reputation.

It's important to vet the longevity and history of a CI vendor to ensure they can be trusted to follow your company's requirements and adhere to high ethical standards themselves. As a start, screen for cease-and-desist orders or other related legal conflicts in their operating history.

Brand protection is a key reason that companies establish corporate ethics. You are, of course, responsible for adhering to your company's ethical guidelines to protect the brand. Likewise, the discipline of CI has its own ethical guidelines established by the organization of Strategic and Competitive Intelligence Professionals (SCIP) to protect the CI brand. The net: Follow both your corporate ethics and CI-specific ethics. The credibility of the guidance you provide to your leadership depends on it.

Even within these guidelines, navigating ethics takes care — especially when collecting competitor information that, while you don't believe it to be a corporate secret, isn't shared openly. Pricing, salesforce compensation, development and marketing timelines, bundling strategies and so on may not be corporate secrets. But each is more protected than other information that's available in public documents.

For example, a B2B contract may not be a corporate secret, but the issuer may not want it shared with competitors. You may want the pricing information in it, but CI ethics dictate that you don't misrepresent yourself or your purpose to get it. And, specific to pricing, if your company is in a dominant position, asking vendors for pricing information and acting on it may be viewed as anticompetitive.

Additionally, as with the legal aspects of CI, it's important to consider ethics from the perspective of the culture in any country where you will collect CI. Some countries set a higher ethical bar in collecting CI than others, requiring additional care — and potentially different methods, such as face-to-face interviews vs. phone-based ones — in your inquiries. This must be factored into your timelines and expectations.

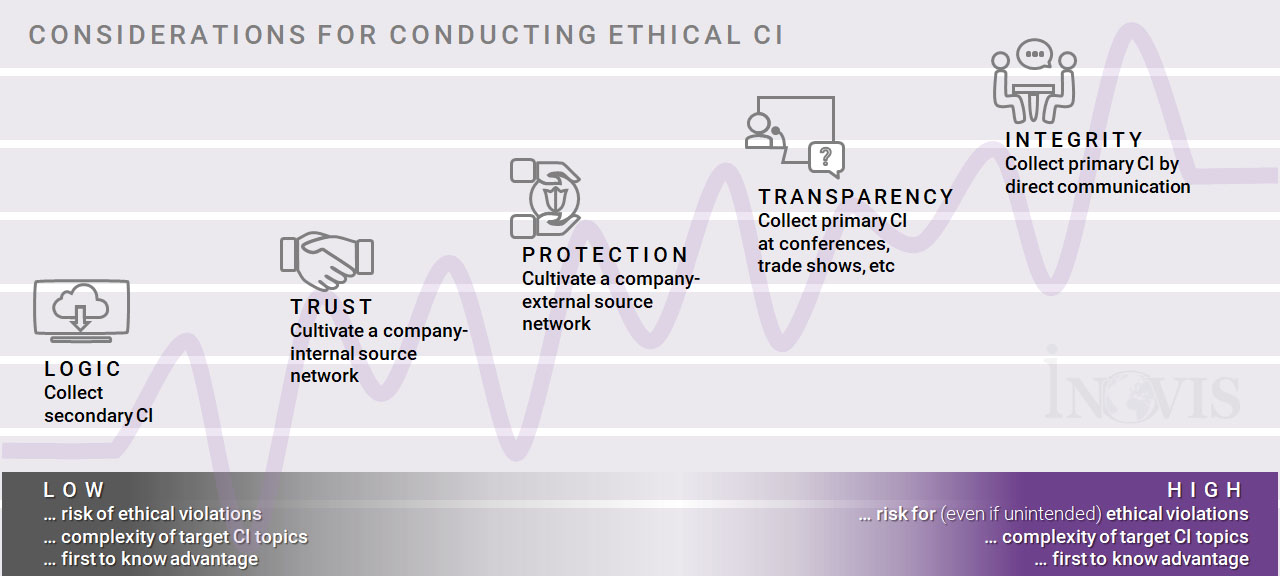

Getting CI from publicly available sources, the public domain or open source, is the simplest CI work. It carries little to no risk of CI ethics violations. Of course, you or any competitor can easily do this — so the first-to-know advantage is minimal. Ethical considerations still apply: For instance, when you request gated content that requires registration, ensure that you don't misrepresent yourself, and allow the provider to decide whether to give it to you. If the provider chooses to not give you the information, you may want to consider engaging a third-party provider to request it themselves and summarize it for you.

Collecting CI from internal company sources, such as field or support employees, also is generally low-risk. However, the employees who contribute insights should follow all legal and ethical guidelines. For instance, employees hired from a competitor must honor any nondisclosure agreement signed with the previous employer and should not be pressured to disclose information that would violate that.

With external sources, using a give-and-take approach (both seeking information from external sources when needed and sharing information with them to keep an active dialog and maintain their willingness to help you) can be used to gather intelligence, as opposed to acquiring intelligence in a purely opportunistic way. This carries slightly higher risk, requiring adherence to all ethical and legal guidelines in any information that you share.

Events are rich environments for collecting information on competitors. They also provide more opportunity for CI ethics violations. Often, new product iterations are unveiled and key announcements are made. These are excellent opportunities to query competitors about their latest products, what's in the pipeline or what new corporate announcements mean for the business. It's OK to approach booth representatives to ask. It's not OK to pretend to be someone else, like a customer, when you do it.

Misrepresentation now can lead to problems later. Leave it to the representatives to share what they're comfortable with. And using a third-party vendor who's not tagged with your company badge can be helpful at times. Your vendor must not misrepresent herself, but she doesn't need to disclose you as a client.

In the world of CI, the term primary intelligence refers to information that comes directly from an original source, such as phone interviews, emails or face-to-face interactions. This work yields the highest first-to-know competitive advantage — and requires the greatest care in adhering to CI ethics.

Ethics dictate that you don't misrepresent your identity or intent when collecting this information. It can cast a shadow on your corporate brand, the brand of the CI discipline and the integrity of the insights you've gathered. Expressing honest interest in the topic usually is enough to get more information.

As a sound CI practice, conduct your analyses based on information triangulated from multiple sources, including open source, subscription, syndicated and primary, to create meaningful insights about the competitive landscape. Lying, misrepresentation and theft simply aren't required — and they are unacceptable.

CI ethics sounds rightfully complex. Staying within the guardrails to ethically practice CI requires care, but there is a common principle that runs beneath the complexity: If it feels wrong, it probably is. Remember the headlines approach: "If you don't want your mother to see it in the news, you probably shouldn't do it. Don't lie, cheat or steal to gain information on your competition. Follow applicable laws and ethics guidelines when you seek information that isn't publicly accessible, and you'll be ready to reap the benefits of ethically obtained CI.

Marc Limacher started INOVIS in 1992 as a boutique primary CI specialty firm in Palo Alto, CA, specializing in the pharma/medtech, digital health and IT industries.

Larry Fauconnet, Senior Director of Competitive Insights & Strategy focusing on IT, Telecommunications, and Digital Health, leverages 30 years of competitive intelligence and strategy experience to assist clients in understanding and positioning themselves more effectively on the competitive landscape.